In a previous post, I discussed Meir Soloveichik’s shifting position with regard to interfaith dialogue. At that time, I was merely excoriating a Rabbi for feteing Mitt Romney against his better judgment. However, Soloveichik’s positions have taken on new importance. Rumor has it that he’s a leading candidate for the post of Chief Rabbi.

Chief Rabbi Soloveichik would bring with him distinguished yichus, eloquence, charisma and intellect. His public profile and ability to intervene in politics and the public sphere could make him a fitting successor to Sacks. Inevitably, his previous polemics and political positions will be vetted. His encomium to Mitt Romney is almost incidental in this context– it’s a Facebook status in an election year. Public figures can learn to soft peddle their obvious politicking. The referendum isn’t going to focus on Soloveichik’s confused utterances about Mormonism. Instead, people will be polarized by his extremely lucid position on hate.

Soloveichik’s piece “The Virtue of Hate” was published in First Things. For the uninitiated, First Things is a religious neoconservative Journal which asks recently reminded us that “secularizing and de-Christianizing forces are at work in our current conflict with the federal government’s health insurance mandate.” Another piece from a month ago helpfully informs us that “there does sometimes seem to be a strong causal connection between child sex abuse and later same-sex attraction.” First Things maintains a patina of sophistication, reviewing scholarly works by guys like Anthony Grafton while chiding us to remember “the pious underpinnings of Western scholarship.”

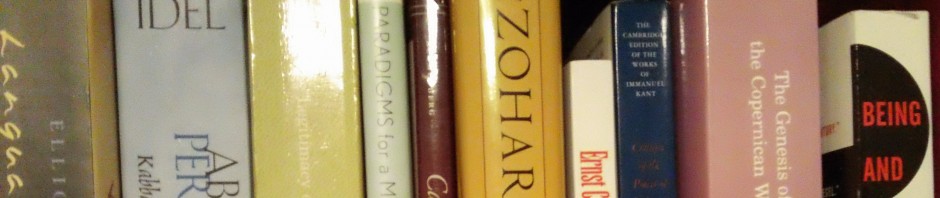

In any case, Soloveichik’s piece was only the beginning of a long relationship between First Things and the an in house YU contingent of neo-cons. In the current issue, we can read Shalom Carmy on the “limits of liberalism” and read a blog post about a recent issue of the Modern Orthodox Journal Tradition, editor, Shalom Carmy. YU students like Alex Ozar and David Lasher have rotated through internships at First Things. Along with conservative think tanks like the Tikvah fund, First Things offered an intellectual home. For some Centrist Orthodox Jews, the heady mixture of intellectualism with conservative religious values must’ve seemed quite simpatico. We can ask whether the intoxicating mix of culture wars and Remi Brague is the right mouthpiece for a Jewish public figure. But these kind of insinuations only take us so far. Soloveichik’s piece should be read on its own merits.

Beginning as it does with the cultural figure of Simon Wiesenthal,“The Virtue of Hate” quickly moves to Dennis Prager. Wiesenthal can’t forgive a pathetic, dying Nazi. He asked a symposium of people whether his failure to forgive was the right thing to do. Commenting on this, Prager “was intrigued by the fact that all the Jewish respondents thought Simon Wiesenthal was right in not forgiving the repentant Nazi mass murderer, and that the Christians thought he was wrong.”

Soloveichik’s choice of cultural figures is a tell. In some sense, he claims the moral authority of the Holocaust, puts himself in the shoes of the survivor, and cashes it out with conservative culture wars.

Along the way, he manages to violate the precept of not engaging in interfaith dialogue.

There is, in fact, no minimizing the difference between Judaism and Christianity on whether hate can be virtuous. Indeed, Christianity’s founder acknowledged his break with Jewish tradition on this matter from the very outset: “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ but I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven; for He makes His sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous. . . . Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” God, Jesus argues, loves the wicked, and so must we. In disagreeing, Judaism does not deny the importance of imitating God; Jews hate the wicked because they believe that God despises the wicked as well.

In between the exegesis of the gospels, Soloveichik manages to squeeze in an essentialist line about Jewish and Christian conceptions of God. Confrontation is once again honored in the breach.

There is a wonderful bit of Jewish lore concerning the giving of God’s Torah, in which God is depicted as a merchant, proffering His Law to every nation on the planet. Each one considers God’s wares, and each then finds a flaw. One refuses to refrain from theft; another, from murder. Finally, God chances upon the Jewish people, who gravely agree to shoulder the responsibility of a moral life. The message of this midrash is that God’s covenant is one that anyone can join; God leaves it up to us.Consider for a moment the extraordinary contrast. For Christians, God acted on humanity’s behalf, without its knowledge and without its consent. The crucifixion is a story of a loving God seeking humanity’s salvation, though it never requested it, though it scarcely deserved it. Jews, on the other hand, believe that God’s covenant was formed by the free consent of His people.

This is great homiletics mixed with another talented rehearsal of other people’s religious principles. Sadly, there’s also a glaring inaccuracy. Another wonderful bit of Jewish lore concerning the giving of the Torah has God threatening the Jewish people with death if they don’t accept it (Shabbat 88). Jewish texts don’t necessarily “believe that God’s covenant was formed by the free consent of His people.” If it was all volitional, what was wrong with the golden calf, Korach or the spies? If its all a democracy, how come the religious “courts can beat people extrajudicially?” There have been many valiant attempts to square the circle of Halakha and democracy. Soloveichik makes no such attempt, he just papers over the problem.

The torrent of essentialism mitigated only by lack of knowledge of Hazal continues. “To my knowledge,” Soloveichik says, “not a single Jewish source asserts that God…loves every member of the human race.” This assertion papers over every universalistic statement in Judaism. To find just one, “Jewish source” Soloveichik can open the siddur to Pirkei Avot 3:14 which reminds us “beloved is man for he was created in the image of God.” (Soloveichik later quotes this very Mishnah!)

Judaism has both universalistic and particularistic statements. Similarly, the Torah is viewed both volitionally and as a divine fiat. Hypostatizing one element of the Jewish tradition, identifying it with the Jewish tradition and then contrasting it to Christianity (similarly boiled down) constitutes an out of control essentialism.

Whence the essentialist contrast of love and law? Where have we heard that Judaism hates which Christianity is all about love? This dichotomy isn’t a staple of the Jewish tradition. It’s a staple of Christian theology. A common Christian rhetorical maneuver opposes the sterility of the law with the magical bonds of love. In his Early Theological Writings Hegel famously excoriates Abraham (who sets the tone for all subsequent Judaism). “The first act” of Judaism “is a disseverance which snaps the bonds of communal life and love.” “He carefully kept his relations” Hegel remarks dismissively “on a legal footing.”

The appropriation of the moral authority of the Holocaust at the beginning of “The Virtue of Hate” makes sense only in context of this theological commonplace. Soloveichik is biting the bullet. Yes– he tells his Christian interlocutors, you were right about Judaism. But beyond this validation lies a critique. After the Holocaust, Judaism (which Christian theology correctly diagnosed) turns out to have unique moral claims. Suddenly, like Wiesenthal, we are the ones doing the judging. What’s subtle is how Soloveichik lets his Christian neocon readers join him in the tribunalization.

As we flip to the end of the article, we aren’t talking about Nazis, but about the peace process.

Archbishop Tutu, who, as indicated above, preaches the importance of forgiveness towards Nazis, has, of late, become one of Israel’s most vocal critics, demanding that other countries enact sanctions against the Jewish state. Perhaps he would have Israelis adopt an attitude of forgiveness towards those who have sworn to destroy the only democracy in the Middle East. Yet forgiveness is precisely what the Israeli government attempted ten years ago, when it argued that the time had come to forget the unspeakable actions of a particular individual, and to recognize him as the future leader of a Palestinian state. Many Jews, however, seething with hatred for this man, felt that it was the Israeli leaders who “knew not what they were doing.”

The identification with the Jews is complete. Christian neocons are pro-Israel, they’re able to hang with the Jews on this important issue. By “hating like us” (as Joe Kennedy said of Bobby) they can transcend the moral problems raised by that mise en scene of the Holocaust. The Wiesenthal moment isn’t about Wiesenthal vs. Nazis. The whole scene is a coded struggle between Dennis Prager and Yitzhak Rabin.

There are moments in Soloveichik’s article that make eminent sense. I’m with him when he says “we will not soon forgive the actions of a man who, as he sent children to kill children, knew all too well just what he was doing. We will not– we cannot-ask God to have mercy upon him.” Suicide bombing remains a reprehensible tactic, and posthumous attempts to clean up Arafat dishonestly gloss over a legacy of terrorism and violence. But putting this commonsensical appeal amidst a theological meditation on Nazis just detracts from its power. We don’t need to posit a false equivalence between terrorism and annihilationism to know not to be terrorists. And Christian parents hate people who kill their kids too. Finally, no one really has Arafat in their prayers. If they believe that God can forgive Arafat, thats more an expression of theological nominalist confidence in God than a ringing endorsement of terrorist Jihad. In Judaism, the Sanhedrin has to know how to kosher a lizard. In Catholicism the priest has to know how to save a terrorist.

Soloveichik is probably right not to have sympathy for Arafat. He’s also refreshingly eloquent for this kind of pro-Israel argument. Additionally, “The Virtue of Hate” shows homiletic flair in its use of Jewish (and New Testament) texts. Some of the formulations have real merit (“The essence of a religion can be discovered by asking its adherents one question”) and bespeak a singular talent for framing issues creatively, refreshingly and memorably. “The Virtue of Hate” is not without virtues.

Yet, all in all, the stakes of “The Virtue of Hate” are just too high. Its about Judaism vs. Christianity, love vs. hate and the Holocaust. And what do we get from that? Don’t like Arafat? Listen to Dennis Prager? Don’t pray for bad people? A lot has been brought in to justify a little.